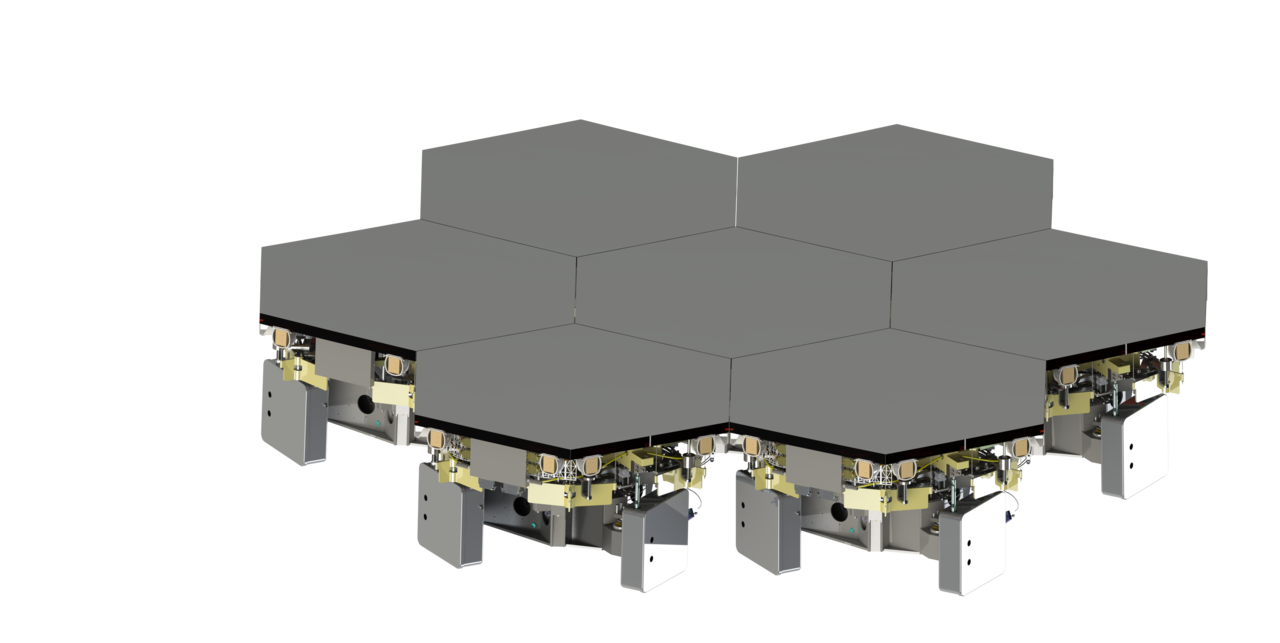

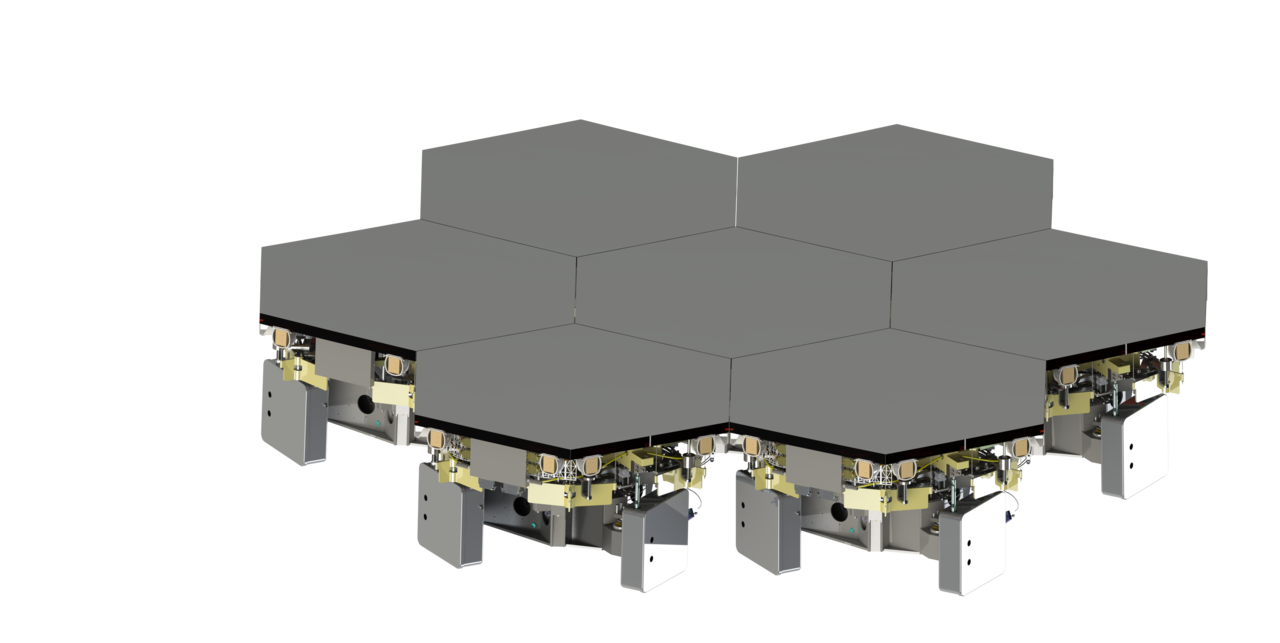

Part of TMT's Segmented Primary Mirror, showing the close packing of the glass segments - Image Credit: TMT International Observatory LLC

Part of TMT's Segmented Primary Mirror, showing the close packing of the glass segments - Image Credit: TMT International Observatory LLC

Pasadena, CA - Last month, I talked with the India-TMT Optics team and one of their industrial partners, Optica. We discussed their work for TMT’s primary mirror, for which India is providing 84 of the 492 pieces of polished glass ceramic.

As explained in one of our blog interviews, this glass ceramic is made of a special recipe which maintains its shape even as the surrounding temperature changes - this is important because it gets cold at the top of the mountain where the telescope will be located.

Elsewhere on this blog, I’ve also discussed how the raw glass ceramic is polished to the correct optical prescription. We then grind the glass ceramic into hexagonal segments, to close-pack the pieces as closely as possible together.

This grinding of the glass ceramic, without damaging the edges or main surface, is very hard to do. So, we've asked Optica to figure out how to do this.

One of the first challenges is to determine how to hold the piece of glass ceramic firmly in place. If we use mechanical clamps alone, we partly loose grip once each of the hex "ears" is cut off.

Optica's choice is to use a “vacuum-chuck” assembly. The vacuum holds the central glass piece in place, as well as the “ears” which are being ground away.

Here's what the initial setup looks like to demonstrate that the vacuum holds correctly. the glass here is just a sample test piece. The

Test setup for assessing whether vaccum adequately holds sample glass in place - Image credit: Optics & Allied Engg. Pvt. Ltd. / TMT-India

zones with the black O-ring are all evacuated.

This vacuum approach worked well. Now that we know how to hold the glass, we can look into how to grind it.

Optica’s plan is to start with a smaller piece of practice glass ceramic than the full-size segments to go on the telescope. Here’s the layout they are using.

Test setup to develop tooling and cutting parameters for hexing of TMT's Primary Mirror glass - Image Credit: Optics & Allied Engg. Pvt. Ltd. / TMT-India

On top is the glass ceramic. Below that are the O rings. Below the O rings is a supporting aluminium plate. The multiple small circles that you can see are the pockets in the aluminium plate. These circles increase the evacuated volume, to hold the glass ceramic more reliably in place in case of any slow leak in the vacuum. Mechanical clamps are used, but they are on the outside of the "ears", so that even once the "ears" are cut off, the remainder of the glass ceramic is still held in place by the vacuum.

Below is a photo of grinding the practice glass ceramic. This glass ceramic is held by vacuum again, although we can't see the O-rings because they are covered by the white cutting fluid.

Grinding of circular piece of practice glass into a segment - Image Credit: Optics & Allied Engg. Pvt. Ltd./ TMT-India

Here's what the finished practice segment looks like.

One nuance here is that the vertical edges of the glass ceramic also need to be very precisely ground. In the following photo, you can see that is indeed the case, and there are no broken edges. And even though the width of this piece of glass ceramic is less than for the full segment to go on the mirror, the thickness is nonetheless the same as the full segment. So, we have good confidence now that we can grind the full thickness correctly.

The vertical edges of the practice glass have been very precisely ground - Image Credit: Optics & Allied Engg. Pvt. Ltd. / TMT-India

We need to carefully measure all the dimensions of the hexed glass ceramic. To do that, Optica is using a coordinate-measuring machine, which has a sensor mounted on the tip of a robotic arm, and which can reach not just the top face, but also the side edges as well.

Measuring the dimensions of the segmented practice glass - Image Credit: Optics & Allied Engg. Pvt. Ltd. / TMT-India

Next, Optica will scale up to cut full-width glass ceramic. Once fully refined, the technical details will be shared with our India-TMT Optics team, who will start grinding the hexagonal segments that will go into the telescope. That work will be done at the new India-TMT facility on the outskirts of Bangalore.

Even in these daunting times, the promise of TMT continues to inspire its many contributors, including the Optica team that I’ve highlighted here, to keep doing the challenging and exciting work that will eventually bring us a clearer picture of our Universe.

Acknowledgements

My thanks to the team at Optica, to S. Sriram and ITCC’s Optics team, and to Glen Cole (Lead Fabrication Engineer at the TMT Project Office).